- Wasted

- Plastic Raft

- Wrecked

- Database Addiction

- Endless War

- Evil Media Distribution Centre

- Invisible Airs

- Coal Fired Computers

- Database Documentry

- Aluminium

- Lungs

- MF2012

- Requiem for Cod

Found Stories

Saturday 18 July 2015

No More Oil on Canvey Soil

In 1973 there were protests from Canvey Island residents when the then Secretary of State for Environment, Geoffrey Rippon, gave the all clear for a second oil refinery to be built on the Island by Occidental Petroleum; the fact that Rippon, to go ahead with this, over-ruled his inspector's decision only riled up the islanders more so.

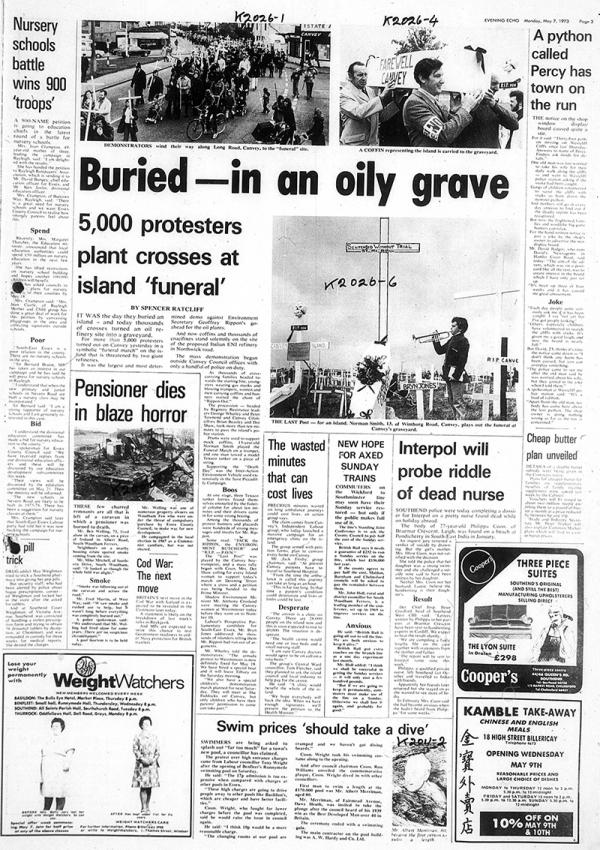

At one of the protests, according to the Evening Echo (Monday 7 May 1973), 5,000 protestors took part in a “funeral” procession where they planted crosses and left coffins on the proposed oil refinery site. Among the placards read: “JACK the RIPPON, the ENVIRONMENT BUTCHER” and “R.I.P. - P.O.N.”

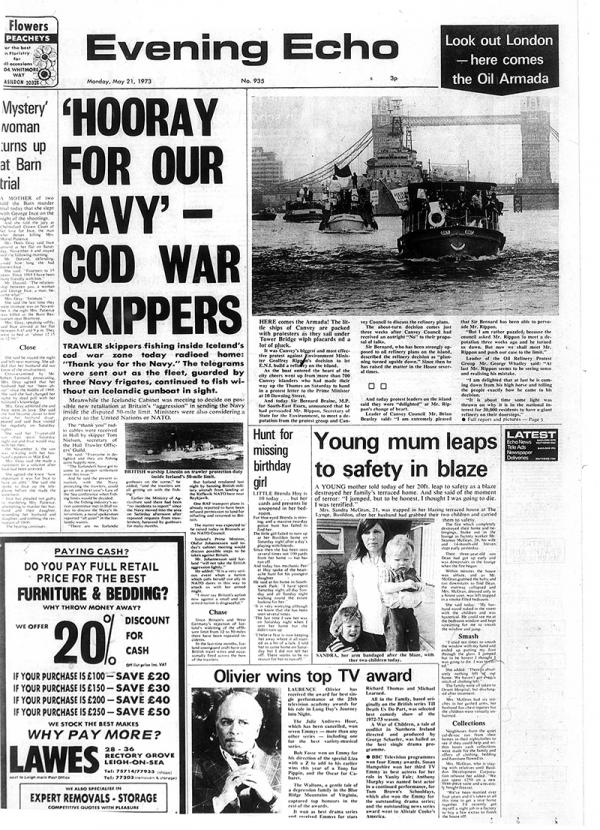

Saturday 19 May, the Oil Armada Heads to London

On Saturday 19 May 1973 700 Canvey Islanders travelled up the Thames to put forward their case by handing a protest letter to the prime minister at 10 Downing Street. Geoffrey Rippon also agreed to speak with a deputation from the protest groups, this was after Canvey Council gave the protestors an outright no to proposed talks three weeks prior. You can see the Canvey residents on the Thames in the image below on the right. There was a full report and more pictures on page three of this edition of the Echo, however page three was missing from the microfilm!

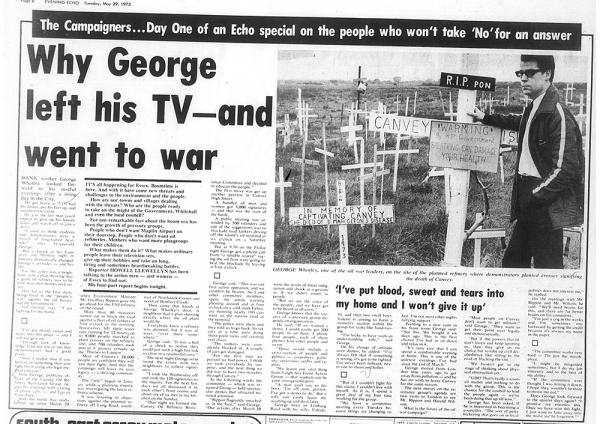

George Whatley

George Whatley was a bank worker in the City who became publicity officer for the Canvey Oil Refinery Resistance Group. To resist the plans for the oil refinery George, along with other members of the group, collected signatures, blockaded road tankers off the island’s oil terminal, marched and planted crosses at the proposed site and through Canvey and journeyed up the Thames in a protest armada. I wonder where George is now and whether he is still on Canvey...

Friday 24 July 2015

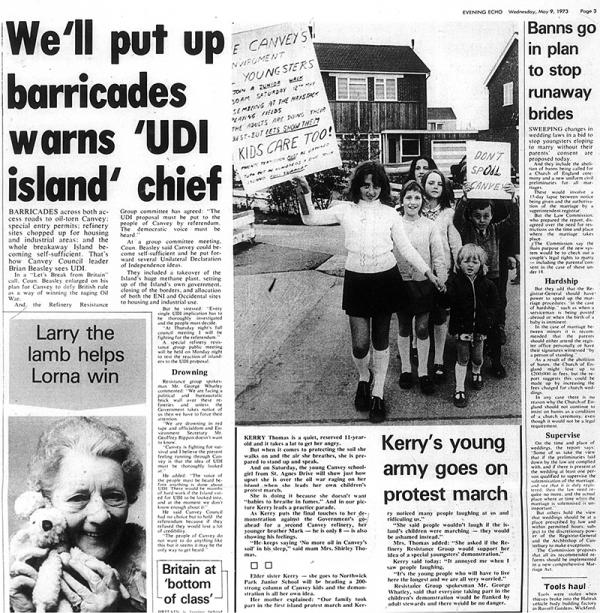

Kerry's young army goes on protest march

Evening Echo, Wednesday 9 May 1973

'Kerry Thomas is a quiet, reserved 11-year-old and it takes a lot to get her angry.

But when it comes to protecting the soil she walks on and the air she breathes, she is prepared to stand up and speak.

And on Saturday, the young Canvey schoolgirl from St. Agnes Drive will show just how upset she is over the oil war raging on her island when she leads her own children's protest march.'

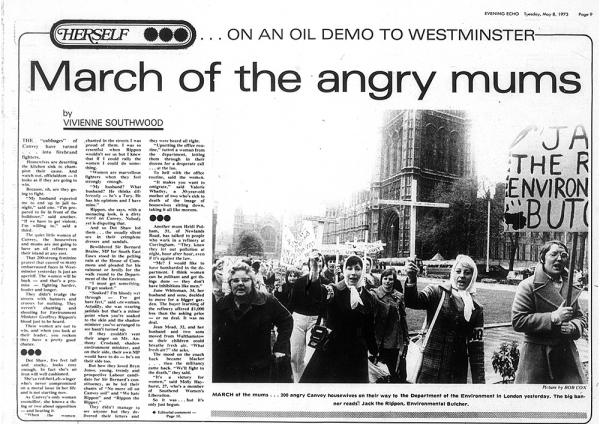

March of the Angry Mums

Evening Echo, Tuesday 8 May 1973

Below is a newspaper cut out about when the women of Canvey Island protested in London about the oil refinery. The caption of the image reads: 'March of the mums . . . 200 angry Canvey housewives on their way to the Department of the Environment in London yesterday. The big banner reads: Jack the Rippon, Environment Butcher.'

The Lightship on the Nore and the Mutiny of 1797

'Out at the sea, far off to the east, lies an area of water know to the sailors as The Nore, from the Old Norse word "nor" which was used to describe sea inlet. Ever since London established itself as an important trading port in the early 18th century, The Nore has been a vital and busy shipping lane.

With an increasing volume of traffic on the River Thames a large number of ships were wrecked on the treacherous shoals and sand-banks which are scattered around the Nore. Because sand-banks tend to shift position from year to year , sailors soon learned that they could not rely on old navigation charts. A gentleman named David Avery struck upon the idea of marking the entrance to the River Thames with a bright lantern, which could be installed on a ship permanently anchored out in The Nore. Avery managed to obtain finances from Robert Hamblin, a seaman from Lynn, and the Nore Lightship was finally built in 1732. This was the first lightship to be established on English waters, and it proved immensely successful.It was described by one author as the "beacon of hope that soothes his sorrows past and marks the home that welcomes him at last."

This os only the start of the story however. Trinity House became anxious that too many lighthouses and ships were falling into private hands, and so they arranged a 61-year lease on the Nore Lightship. The scheme allowed David Avery to collect the bills for the lightship, provided that he paid an annual sum of £100 to Trinity House. This gave Avery the financial security that he wanted, and when the lease ran out in 1794, Trinity House obtained complete control of the lightship.

The Nore Lightship was replaced in 1796, but trouble was new brewing. The country was in economic chaos after four years of Napoleonic was. All foreign allies had either surrendered or defected under the might of advancing French armies, and even Ireland was on the point of rebellion. At home, there was a run on the Bank of England, and William Pitt the Younger was struggling hard as Prime Minister in the face of growing discontent over food shortages. The only obstacle to a full-scale invasion from France was the British navy, and even they were clamouring for better working conditions. The ships in which they served were cold and cramped, and they had no medical facilities to deal with the frequent outbreaks of disease. Wages had not been increased for over 150 years, and were rarely paid anyway.

In February 1797, a group of sailors serving at Spithead near Portsmouth approached a retired admiral called Lord Richard Howe. The seamen held him in high regard, and asked him to press their case in Parliament. When March has passed without reply, the Spithead sailors decided to take more explicit action. They directly petitioned the House of Commons and began a campaign of disobedience. Although they were offered more pay, they decided to hold out for better working conditions. At first the Admiralty agreed, bu the sailors discovered that secret plans had been drawn up to deal harshly with any mutineers. The Admiralty completely lost control as the sailors took over their ships and went on strike, leaving the south coast of England vulnerable to Napoleon's navy,

The government acted immediately. On the 8th May, an Act of Parliament was raised to satisfy the sailors' demands, passing through both Houses and getting Royal Assent all within 24 hours. Since the Spithead rebellion had now achieved all its aims, the navy there quickly returned to normal. Because of poor communications, however, this news took too long to reach the sailors who were stationed in the Thames Estuary. On the 11th May, the Nore sailors mutinied in sympathy with their Spithead colleagues, and seized control of the flagship "Sandwich", unaware that the government had already given in to their demands. This left the Nore seamen in a very difficult position, because they now required Royal Pardons for their mutiny. The authorities were growing impatient with mutineers however, and decided not to concede to the new rebellion.

Many of the Nore sailors deserted, and the uprising became extremely disorganised. Having achieved no progress by the 28th May, the rebels decided to gamble by blockading the River Thames. In retrospect, this was probably a bad decision, because local traders were scared of the effect this would have on their business. The mutineers began to lose their popular support, and this was probably the turning-point of the whole revolt.

The government passed another Act of Parliament to make mutiny a capital offence, and Trinity House deliberately sank all buoys and beacons around the Thames estuary. This meant that the rebels were now unable to escape. On 12th June, with dwindling supplies, they realised that their position was hopeless and decided to surrender. The Nore mutiny had been quashed. The ringleader, Richard Parker, was hanged from the yard-arm of his ship, and with the Admiralty back in control, the navy began its long struggle against the French forces which led ultimately to Napoleon's downfall. Britain had been saved from the brink of defeat, though it is worth reflecting that is the unnecessary mutiny at The Nore had continued a little longer, the history of Europe could have taken a completely different course.

In 1839, the Nore lightship was again replaced. The new ship, known as "No. 14", or "Old Stormy", faithfully serves sailors in the Thames for a century. At the outbreak of the Second World War, it was withdrawn in order to hinder any possible invasion. In 1944, the lightship was towed out to sea near Dover as part of a secret mission, but it was sunk by enemy action. The lightship was never replaced. After the war, a simple beacon was placed at The Nore, and to this day this marks the haunt of Old Stormy.'

Reference:

M.P.B. Fautley, J.H. Garon (2004) Essex Coastline: Then and Now, : Potton Publishing. pp. 208-209

Monday 27 July 2015

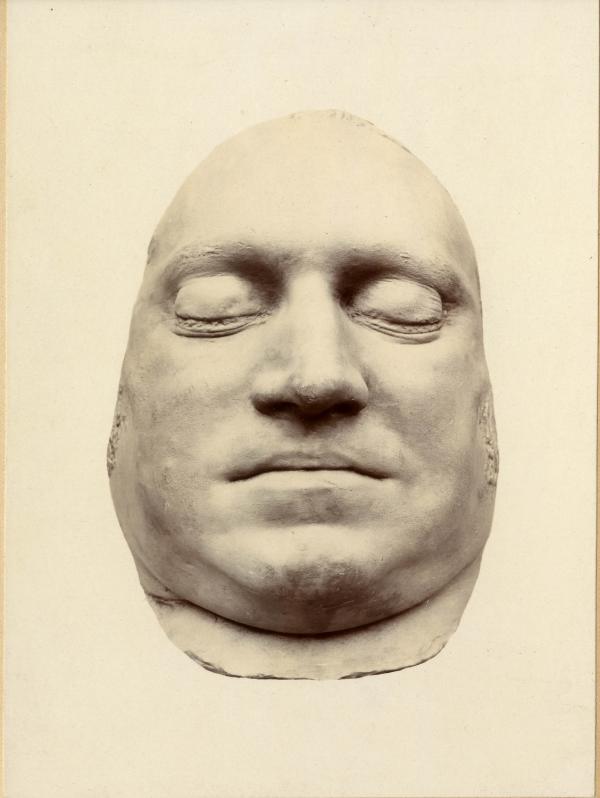

Richard Parker, President

Below is a photo of the death mask of Richard Parker (1767 - 1797) who was President of the Delegates at the Nore. The photo is from the Portrait Collection in the Natural History Museum Archives. The actual death mask was casted by John Hunter, founder of the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons and I believe it still resides at the Hunterian Museum, of which I am trying to confirm. Written on the back of the image is "Death mask of Parker of the Nore".

Reference:

http://www.nhm.ac.uk/natureplus/community/library/blog/2013/03/27/item-o... (last accessed 27/07/2015)

Smuggling in Old Leigh

The earliest reference known of smuggling in Old Leigh is in 1225 when grain was being smuggled out of the area, where it was probably set to be sold abroad without a license. In 1344 there was a series of arrests by an official named Saier Lorimer, the men stole wine and other goods from a vessel which was half derelict near Leigh and which they probably thought was a wreck. In 1394 a John Lemourner and John Greipin of Amiens lost their ship to a privateer off Hadleigh, only three of the crew survived, the rest were killed, and the vessel was wrecked on Thanet. A further 5 dutch sailors and a boy had their throats cut between Leigh and Sheppey by pirates when they boarded a little ship from Haarlem called The Bus, and they only managed to get £100 and a cargo of cloth and tin.

Reference:

H.N. Bride (2013) Old Leigh, Leigh Society : Southend Museums Southend-on-Sea Borough Council. p. 3

Tuesday 28 July 2015

At Leigh Heritage Centre

Karen

Lawrence/Low(?) Ford (low said like how) owned 'the Moss Shop' where the white weed was sold. White weed also was sold on Southend Pier.

Ed

Billet Lane was apparently haunted and the fisherman never used to go up there during dark nights.

The Conduit got fresh water from the spring at the top of the hill and was brought down to various cisterns that could hold around 4000 gallons.

The gate was opened in order for the community to get water once or twice a day, where women used to queue up with buckets. There used to be quite a large woman who used to push her way to the front. This was c.1750-1800.

The only thing they saved from the Peter Boat fire in 1892 was a plum pudding. The landlord and his nephew knocked through the wall next door to the Peter Boat to save the landlord's wife and children as they were upstairs and couldn't get down. The fire started because the landlord and his nephew were drinking after hours and knocked over an oil lamp. The vast majority of houses were wooden so they were easy to catch alight.

When they laid the train tracks in the 1800's a lot, if not all, of the Crooked Billet's out houses went.

Opposite where Leigh Heritage Centre is now used to be Cook's Place 'Ye Cosy Cafe'

Apparently white weed is popular in Japan for the lining of coffins.

Ships that were built in Leigh went to the Spanish Armada and the Dutch Wars.

There used to be a pottery by the Grand Hotel that began producing before 1845. There were potters listed living in Leigh from 1851.

The letters of Julianna Stuart-King that date back to 1874, of which Stuart mentions (Found Speakers), were to her son Robert Stuart and always began 'My dearest old Bob'...

A couple of the letters speak of a dog called Ben. Julianna put Ben on a train that only took him to Fenchurch Street. She put a label around his neck with directions as to where he should go, which was to Robert in Grimsby via King's Cross. She writes how Robert 'never made any remark on the beautiful label'. As well as directions it asked that the dog was given water and said 'I bark pound but never bite'.

The Houseboats of Leigh-on-Sea

It is unclear when the houseboats first appeared on the estuary at on the creek at Leigh. But in 1921 the Council were told that the inhabitants of the houseboats were drawing their drinking water form a tap that was installed on Bell Wharf solely for the fisherman. Other than this exception the houseboat residents were self sufficient, with lamps fuelled by kerosene or paraffin, the cooking was done on coal fired Kitchener ranges - which could also act as heating with the front panels removed - or with paraffin cookers. Rain water would be collected but was not sufficient for all their needs. They paid the fisherman 10/- a quarter for the water but because it was only meant to be for the fisherman the Council put a notice discouraging unauthorised use of the water. But this did not deter anyone so the Council went further and employed someone to stand all day by the tap, when the Council member of staff went home at midnight the people living on the boats came out to fill up their containers (pp. 6-7)

The houseboats continued to increase throughout the 1920s and 1930s and eventually there would be around 200. However not all the houseboats were lived on all year round and were used as holiday homes for Londoners. This group was known as weekenders.

'A report by the Medical Officer for Health at the end of 1922, showed that the number of houseboats moored in the creek had increased in twelve months from 18 to 36. He expressed in correspondence between himself and the Medical Officer of the Port Sanitary Authority in London, concerns arising from the use of these boats.

For the next two years the houseboats continued to grow in numbers and a community and way of life began to form. The children went to the local school, the milkman delivered twice a day and the postman called at 8am, 11am and 4pm. Apart from personal mail the only demand for money to be received came from Southend Council who charged rates for resting their walkway on the foreshore.' (p. 7)

The Salvation Army owned some land at Hadleigh which was purchased in 1890 at £12,000. This land stretched all the way over the downs and onto the creek. This meant that when the tide was out and the houseboats rested on the mud, the Salvation Army were the landlords on that particular part of the creek. In 1925 Southend Council wrote to the Salvation Army with the following suggestions:

• the houseboats should be charged 2 guineas for each boat's mooring

• that the Salvation Army should have the right to terminate any agreement they had with the houseboat owners

• the council asked the Salvation Army not to issue anymore licenses for the mooring of craft on the creek

• they also suggested the Salvation Army serve notice on the present moored houseboats in the creek

This issue rolled on for a number of years and the Salvation Army never charged the houseboat owners any rent.

In 1929 the Council tried a different approach and offered to buy the land that the Salvation Army owned so that they had control of the houseboats. However the Salvation Army want the Council to buy to the West of the boundaries as well as up to a point known as Pinnett Dock along with the area in contention. The same year the Council were able to gain more powers o deal with the removal of the boats but they still remained, steadily increasing.

In July 1936 the Council pushed ahead and ended up buy the land in question for £33,500 from the Salvation Army to ensure "that the land is not used for purposes detrimental to the borough". And following completion of the transition the committee recommended "that the Town Clerk be authorised to take all necessary steps with a view to effecting the removal of all houseboats".

It was thought that many of the weekenders who owned houseboats perished during the blitz in London.

'Although there had been a natural steady decline in the number of boats and families living by Leigh Creek - some had already moved their houseboats up river to Canvey Island or Benfleet Creek, there were still a substantial number of houseboats moored along the towpath.'

At the beginning of 1948 the Council managed to move or had the owners take away 55 houseboats, later in 1948 there were 96 more that were removed. This left around 27 houseboats, 12 were own by Leslie Warland.

One of the more popular houseboats was the St Kilda (originally owned by Mr and Mrs Palmer). St Kilda sold sweets to the children from other houseboats and tea and coffee to visitors to Old Leigh as well as to the troops based in the area during the war. In March 1948 the St Kilda was the subject of a Sheriff's Warrant and was dismantled at the cost of £190 - paid for by the council in 1950.

Rosa John was dismantled at a cost of £145 - less £7 for the value of materials recovered.

Ermuden was dismantled at £98 - less £4 18s 0d value of materials covered.

It appears that it was 1950 that saw the final chapter of the houseboats, their history and for those that lived in them on Leigh Creek from 1921.

In 1948 the Southend Corporation had obtained enough legal powers to remove the boats from the seawall at Leigh-on-Sea. Better quality houseboats were towed upriver to Canvey or Benfleet where their owners continued to live on their houseboats. However some were simply just left to rot away. (p. 57)

Here is a list of names uncovered by Carol Edwards out of the approximate 200 houseboats moored at Leigh-on-Sea between 1920-1950. Perhaps the others will remain unknown...

• Adventurer

• Ark

• Baden Powell

• Banshee

• Ben Bow

• Braemar

• Cleopatra

• Comet

• Daisy

• Daunley

• Edith

• Eileen

• Endeavour

• Ermuden

• Estol

• Ganges

• Glen Rosa

• I Can Do It

• Ilka

• Iron Duke

• Jeanette

• Lady Quirk

• Maria

• Minorette

• Mistletoe

• Oakdale

• Penguin

• Phyllis

• Rosa John

• Sarado

• Sea Gull

• Shamrock

• Sidney

• Silver Town

• St Kilda

• Taj Mahal

• The Optimus

• Wait on 2

• Wait on 1

• West Kent

• WinVic

Reference:

Carol Edwards (2009) The Life and Times of the Houseboats of Leigh-on-Sea, Publisher Carol Edwards. pp. 1-10 & pp. 57-64

Thursday 30 July 2015

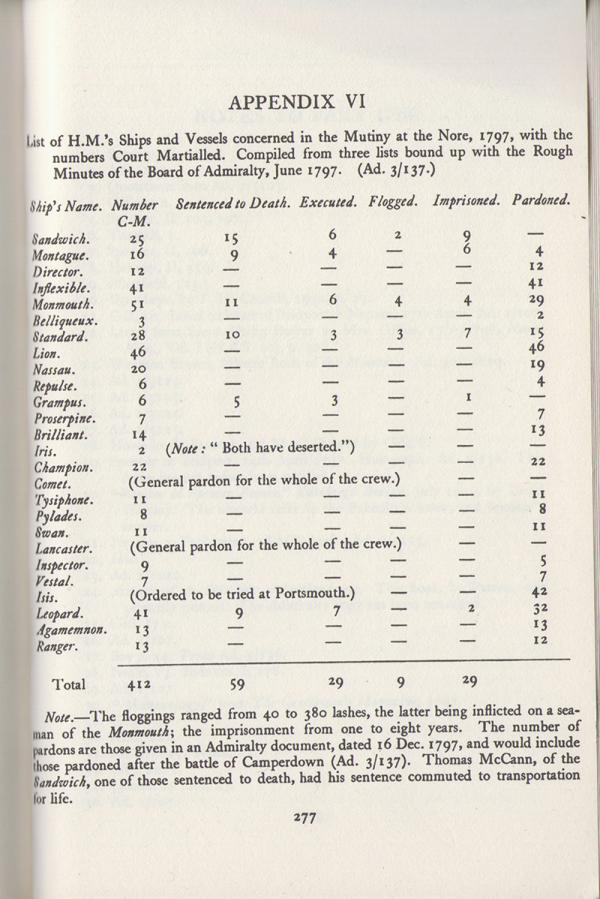

A list of H.M. Ships and Vessels concerned in the Mutiny at the Nore, 1797, with the numbers Court Martialled. Compiled from three lists bound up with the Rough Minutes of the Board of Admiralty, June 1797.

Below is a list of the H.M. Ships and Vessels concerned in the Mutiney at the Nore, 1797. The list included the number of those Court Martialled as well as how many that were sentenced to death, those who were actually executed, flogged, imprisoned and pardoned.

'The floggings ranged from 40 to 380 lashes, the latter being inflicted on a seaman of the Monmouth; the imprisonment from one to eight years . . . Thomas McCann, of the Sandwich, one of those sentenced to death, had his sentence commuted to transportation for life.'

C.E Manwaring (2004) The Floating Republic, S. Yorkshire: Pen and Sword. p.277

Saturday 1 August 2015

Oysters at Leigh

The trade in oysters grew rapidly in the 17th century and much of the foreshore between Leigh-on-Sea and Thorpe Bay were taken up by oyster-beds. An incident in 1724 demonstrated the importance of the industry during that time when a crowd of about 500 fisherman from Queenborough in north Kent raided the oysters at Leigh. They seized as many oysters as they could carry and then took them up to London to sell them. The fisherman at Leigh not only had their stocks raided and depleted but they were also devastated by the resultant drop in prices because of the sudden glut of oysters on the market. Eventually the invaders were taken to court and ordered to pay around £700 in damages.

Reference:

M.P.B. Fautley, J.H. Garon (2004) Essex Coastline: Then and Now, : Potton Publishing. p. 215

Tuesday 4 August 2015

Mines on the Estuary

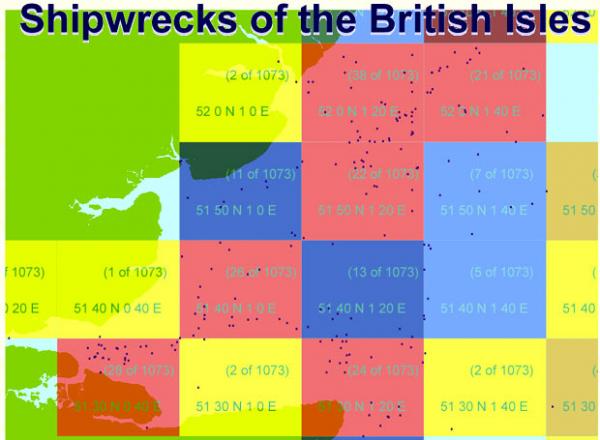

'The map below shows a few of the ships sunk from just one cause - mines - and in just one area: the Thames Estuary. A small but chilling reminder of the wartime toll of seamen in the seas around Britain and Ireland. In an area less than 100 by 40 miles, sea mines accounted for more than 200 ship losses. In the seas around Britain and Ireland as a whole, ship losses from mines totalled nearly 1,100 - from more than 20 countries - and with the loss of more than 5,000 lives.'

Each coloured square shows you how many vessels out of the 1073 across Britain were sunk in that specific area.

Reference:

http://www.shipwrecks.uk.com/news.htm (last accessed 04/08/2015)

The Loss of the Princess Alice

On the evening of 3 September 1878, the Princess Alice was returning up river from Sheerness with about 700 passengers. Many of the passengers were listening to the band as the steamer approached Woolwich unaware of the impending danger as the steam collier Bywell Castle approached them en route to Newcastle to take on coal for Alexandria.

To Captain Harrison on the bridge of the Bywell Castle, the Princess Alice appeared to be coming across his bow, making for the north side of the river. He altered course accordingly, intending to pass safely astern of her. But the passenger steamer suddenly changed course directly into the path of the oncoming collier. The captain of the Princess Alice, realizing that a collision was imminent, attempted to change course but it was too late and the bows of the collier struck the steamer just forward of the starboard paddlebox almost cutting her in two. The Princess Alice sank in less than four minutes and over 640 people were drowned making it the worst river disaster on record in Great Britain.

The subsequent Board of Trade inquiry concluded that Captain Grinstead of the Princess Alice (who was among those drowned) was to blame as he had run directly across the path of the Bywell Castle contrary to the 'Rule of the Road'.'

Reference:

http://www.rmg.co.uk/explore/sea-and-ships/facts/faqs/ships-and-vessels/... (last accessed: 04/08/2015)

Thames estuary dredging takes toll on fish stocks

November 8, 2013

'Britain’s biggest port, which opened this week in the Thames estuary, has the potential to revolutionise the way goods are brought in to the UK and transported around the country.

But while the £1.5bn London Gateway project has been lauded by ministers and civic leaders for its impact on industry and employment, some members of Kent and Essex’s fishing community are worried.

Their concern stems from the deep water channel that DP World, the port’s owner, dredged 100km out into the North Sea to allow the world’s biggest ships to dock at its quayside.

By stirring up silt, some fishermen fear it has choked the sensitive estuary habitat. Paul Gilson, a Southend fisherman and member of the executive committee of the National Federation of Fishermen’s Organisations, said fish and shellfish stocks had fallen from healthy levels six years ago, particularly the Dover sole that are concentrated in the estuary.

“People are not going to sea so often because they’re not catching anything. Six years ago we had increasing stocks of all types. Now we’re down to just sea bass and a few skate, which don’t appear to be affected by the dredge.”

Mr Gilson, whose family have fished for 200 years, said his £400,000 turnover had fallen to £30,000 over the period. “None of us expected the size of the problem.” Now he worries that dredging may need to take place regularly to prevent the channel filling in.

The port, which has closely monitored ecological conditions in the estuary, has set up a compensation scheme for fishermen suffering dwindling catches. But a port spokesman said fears about continued dredging were misplaced, since the fast-flowing Thames was “self-scouring”.

Evidence from Princes Channel in the southern estuary, which was dredged in 2008 by the Port of London Authority, appears to back this claim. Richard Everitt, PLA chief executive, said the channel had required no further dredging and “studies suggested it will self-sustain.”

Mr Gilson, meanwhile, is considering moving to the southwest, “because that’s where there’s plenty of fish.”'

Reference:

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/1c5f2ae4-489d-11e3-8237-00144feabdc0.html#axzz... (last accessed: 04/08/2015)

The Bovril Boats, from London to Barrow Deep

• Bexley

• Hounslow

• Newham

• Thames

The above were four motor boats, better known as 'Bovril boats' because of the colour and consistency of their cargo. Each vessel could carry 2300 tonnes of sewage sludge from East London's sewage works and out to the Thames Estuary to areas such as Barrow Deep. Dependant on the weather this would happen on a daily basis and continued from 1887 to 1998. The combined amount dumped by these vessels was 7.5 millions tonnes per year.

This is Bexley:

References:

Milne, R, (1987) 'Pollution and politics in the North Sea', New Scientist, 116(1587), pp.53-58

https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg12817453-700-technology-sludge-di... (last accessed 04/08/2015)

http://www.shipspotting.com/gallery/photo.php?lid=146344 (last accessed 04/08/2015)

Saturday 8 August 2015

Layers of Coal on the Estuary Bed

'The main sources of coal were of course Yorkshire, Co. Durham and Northumberland, the 'black gold' being loaded in the Rivers Tyne or Tees and shipped south to feed insatiable southern industries, millions of domestic grates and hearths in London and the home counties, and later, boilers of steam ships, particularly those of the Royal Navy based as Sheerness, Chatham and Portsmouth. The sheer number of colliers lost is only now emerging with any degree of accuracy . . . and it is no exaggeration to say that the east coast of England is littered with millions of tons of coal that never reached its destination.'

What follows below is a list of shipwrecks on the northern coast of the Thames Estuary, from Foulness Point to Leigh-on-Sea. The list includes their names, destinations, coordinates and dates. All of these vessels were carrying coal:

FREE LOVE, Foulness Point, The Swim. 51.37.10N 01.06.30E, 06/01/1764

GENEROUS FRIEND, Shoebury Ness, near. 51.32N 00.49E, 31/01/1764

FRIENDS GOODWILL, Foulness Point, Maplin Sands. 51.35N 00.55E, 16/11/1812

PLOUGH, Foulness Pont, Buxey Sand. 51.42N 01.05E, 08/02/1827

HARTON, Foulness Point, Sunk Sand. 51.39N 01.20E, 19/09/1827

CALYPSO, Foulness Point, Maplin Sands. 51.35N 01.21E, 01/10/1827

CARLEN, Foulness Point, Whitaker Sand. 51.40N01.08E, 02/02/1830

FRIENDSHIP, Foulness Point, Maplin Sands. 51.35N 00.55E, 16/06/1833

JUNO, Foulness Point, Maplin Sands, Blacktail Spit. 51.31.30N 00.56.25E, 09/12/1853

JANE JACKSON, Foulness Point, Maplin Sands, Blacktail Spit. 51.31.30N 00.56.25E, 10/12/1853

ZEPHYR, Foulness Island, Middle Sand. 51.40N 01.10E, 14/01/1861

GIPSEY, Foulness Point, Barrow Sand 51.38N 01.10E, 20/12/1862

CONFIDENCE, Foulness Point, Maplin Buoy, near. 51.35N 00.55E, 20/08/1876

PORCIA, Shoebury Ness, Maplin Sands. 51.35N 00.55E, 18/01/1881

EMMA & MARY, Foulness Point, Barrow Sand. 51.38N 01.10E, 14/10/1881

THOMAS LEA, Southend-on-Sea, Pier, near. 51.32N 00.42E, 26/10/1882

HONEST MILLER, Southend-on-Sea, Leigh Spit. 51.31.45N 00.40E, 30/09/1885

VICTORIA, Foulness Island, Foulness Sand. 51.39N 01.05E, 06/01/1886

MARY & EMILY, Foulness Point, Maplin Sands, E Maplin buoy, 0.5M NE. 51.34.30N 01.03E, 22/02/1891

LOUISA, Foulness Point, Maplin Sands. 51.35N 00.55E, 24/11/1895

NOTOU, Southend-on-Sea, E Knob Buoy, 9 cables E. 51.32.10N 01.08.31E, 25/04/1940; ex-(MARGAM ABBEY). Her bow was blown clean off when she struck a mine, whilst carrying 3,750 tons of cargo (coal, unspecified). The vessel was completely submerged after sinking.

Reference:

Richard & Bridget Larn, (1997) Shipwreck Index of the British Isles: Index to Volumes 1-3 (v. 3). Edition. Tor Mark Press.

Tuesday 11 August 2015

Notes from conversation with writer and photographer Robert Hallmann, 7 August 2015

Canvey Island

On Canvey Island an entrepreneur, Frederick Hester, bought plots and sold them for £5, £10 and £15. People from London were encouraged to come down with their train tickets paid for them and meals provided. This happened around the turn of last century. Grain was being brought in from U.S. and farmers were becoming bankrupt.

In 1904 Hester became bankrupt.

The same kind of thing happened with the plots at Pitsea and Laindon.

The Red Cow pub has been pulled down on Canvey (date?)

Before the road was built across from Benfleet to Canvey you used to have to walk over the stepping stones at high tide or row over during high tide.

A well used to be at the hub of Canvey life, from Holehaven Road

Canvey used to be called 5 Islands of Cana’s People. (Saxon origin?)

At Canvey Point lots of Roman and Medieval artefacts were found. Amphoras were found that used to carry wine, which would have been imported from Italy. This shows that Canvey must have been a prosperous place.

During Roman times Canvey would have been 15ft higher and would not have been an island.

On Canvey hay used to be brought from the horses onto the barges. Hay was the main industry, bringing it up to London on the barges before people came with the plots.

Canvey used to belong to 9 different parishes including Pitsea, Vange and Prittlewell.

The Lobster Smack on Canvey was mentioned in Dickens’ Great Expectations.

The Revenue and Customs used to stand on a watch tower by the Lobster Smack with binoculars to catch smugglers.

Water has claimed back land near Canvey Point, from photos you can see it used to be farmed fields.

When the Dutch settled on Canvey they built a sea wall and their own church. The English wanted to use the church but they had to have a fist fight in order to use it. The English built their own. (Around early 17th century?)

Foulness

The Broomway at Foulness would have been over land before the Romans. It is parallel to the road and suggests the land has been taken by the sea.

On the Broomway brooms were tied to the top of the sticks along the route in order to see them when the tide was in.

The Broomway goes from Great Wakering to Foulness but used to go from Shoebury to Foulness. There were 7 routes on farmers’ land going off the Broomway and farmers used to take a toll to use their roads.

Three young men were shooting birds on the Broomway and walked into the fog during the Cold War period. They were never seen alive again. Lots of rumours were spread such as that they were abducted by the Russians and that a man was seen with a long overcoat. A Russian Ship was apparently also on the Thames at the same time.

There has been talk about brooms being replaced on the Broomway.

In 1922 there was 479 people living on Foulness.

The church is closed on Foulness.

Cutlass Stone at Clements Church, Leigh

There is a brick built grave next to the entrance of St. Clements Church in Leigh, on top of Leigh Hill. The tomb is of Mary Ellis, who died at the age of 119. On top of it is a big slab with grooves. This is where the press gangs used to sharpen cutlasses, knives and so on. It is known as the Cutlass Stone.

There is said to be a tunnel from the church to the rectors house at the bottom of Leigh Hill where the young men would be smuggled in order to avoid being pressed. If you accepted the King’s shilling this meant you accepted being in the Navy, this could have been put in a drink that would have been bought for you, if you accepted it you accepted the King’s shilling and were pressed into the Navy. This is why glass bottoms were made in the bottom of drinking vessels so one could check the bottom before accepting.

Smuggling

Things that were smuggled:

• Gin

• Brandy

• Lace

• Fine cloths

Became a way of life for some. On paper it would say they were fisherman or oyster catchers.

Two Tree Island, the Dump

Below is a photograph by Robert Hallmann of Two Tree Island when it was a landfill site. The date of the image is not clear however it may have been during the Winter of Discontent, 1978-1979. You can see Hadleigh Castle in the background.

Photograph by Robert Hallmann.

Courtesy of Robert Hallmann, copyright and all rights reserved.

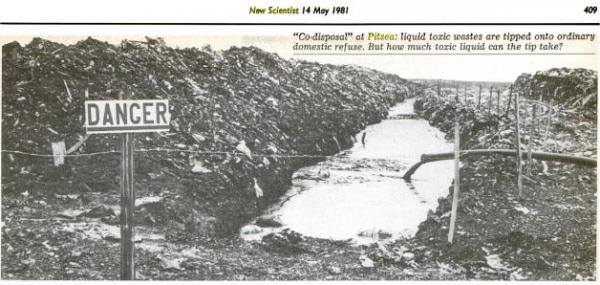

'Co-disposing' on Pitsea Tip, New Scientist 14 May 1981

'One problem of hindering the formulation of waste-disposal strategies is that surprisingly little is known about what happens inside tips. Perhaps the most worrying practice is that of "co-disposing" - dumping both toxic liquids and household wastes at the same disposal site. The liquids are simply poured onto piles of domestic rubbish and left to sink in. Britain's biggest tip, at Pitsea in Essex, has a licence to tip 160 million litres of toxic liquids in this way each year, across 240 hectares of domestics refuse. Opponents of this method claim that we could be producing huge and permanent chemical quagmires. How much toxic liquid can a giant sponge like Pitsea take before it becomes saturated?'

Reference:

Pearce, F., & Caulfield, C., (1981) New Scientist, 90(1253), pp.408-410

Thursday 13 August 2015

Landfill sites

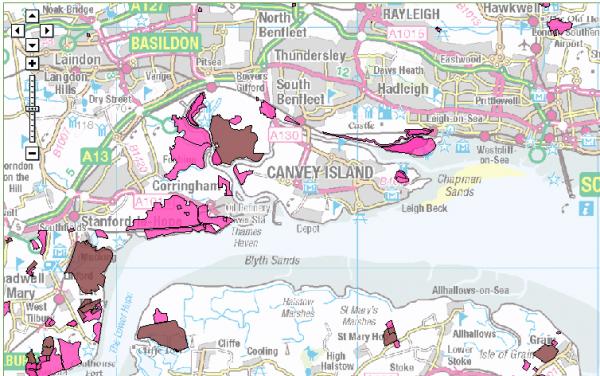

A map of authorised (brown) and historic (pink) landfill sites: to the right of Canvey Island is Two Tree Island, to the top left is Pitsea tip, still in operation; and the bottom left by Canvey is Mucking Flats.

Reference:

http://maps.environment-agency.gov.uk/wiyby/wiybyController?x=570500.0&y... (last accessed 13/08/2015)

Fish in the Estuary

Many of the species of fish in the estuary have returned since the 19th century when we so badly damaged the river pretty much all fishes disappeared. Populations now compared to pre 19th century are probably very low. Those that have been extirpated are sturgeon, sea lamprey and salmon.

- From an email exchange with Joe Pecorelli, UK & Europe Conservation Programme, Zoological Society of London, 06/08/2015

Tuesday 18 August 2015

Layers of Coal on the Estuary Bed, Part 2

JAMES, Thames, The Swim. 51.37.10N 01.06.30E, 23/02/1770

REBEKAH, Thames, 'In the River'. 51.30N 00.28E, 18/01/1771

HAZARD, Thames, 'In the River'. 51.30N 00.28E, 27/01/1771

PRINCE FREDERICK, Thames, The Swim. 51.37.10N 01.06.30E, 26/03/1771

SUBMISSION, Thames, The Swim. 51.37.10N 01.06.30E, 26/03/1771

LOVELY CRUIZER, Thames, 'In the River'. 51.30N 00.28E, 20/10/1773

BETSEY, Thames, Sunk Sand. 51.39N 01.20E, 31/12/1779

HOLDERNESS, Thames, Long Sand. 51.40N 01.29E, 09/03/1798

ARGO, Thames, Nore Sand. 51.28.30N 00.46.30E, 12/12/1815

JEUNE EMILIE, Thames, Long Sand. 51.40N 01.29E, 28/09/1853

TINO, Thames, Long Sand, near. 51.40N 01.29E, 03/10/1853

HAREWOOD, Thames, Mouse Sand L/s, near. 51.32N 01.04E, 04/10/1853

NORFOLK, Thames, Long Sand. 51.40N 01.29E, 07/11/1854

ROBERT, Thames, Tongue Sand. 51.28.22N 01.16E, 01/12/1855

SECRET, Thames, Long Sand. 51.40N 01.29E, 11/09/1857

CHARITY, Thames, Long Sand. 51.40N 01.29E, 12/11/1860

ZEPHYR, Thames, Middle Sand. 51.40N 01.10E, 14/01/1861

DARIUS, Thames, Long Sand. 51.40N 01.29E, 02/11/1861

HENRY, Thames, Shivering Sands. 51.30N 01.05.30E, 20/12/1861

REGARD, Thames, Long Sand. 51.40N 01.29E, 15/11/1862

TELEGRAPH, Thames, Sunk Sand. 51.39N 01.20E, 20/11/1866

FANNY, Gravesend, 3M above. 51.27.30N 00.21E, 05/02/1867

GOSHAWK, Thames, Long Sand. 51.40N 01.29E, 13/09/1868

JESSAMINE, Thames, Mouse L/s, 2M W. 51.32.45N 01.03.25E, 21/09/1869

CARL AGRELL, Thames, Long Sand. 51.40N 01.29E, 23/12/1869

ALDOURIE, Thames, Long Sand, 2.5M above buoy. 50.50.15N 01.40E, 01/11/1872

HURON, Thames, Nore L/s, 1M WNW. 51.28.30N 00.46.30E, 18/08/1876

HANNAH COPPACK, Thames, Sunk Sand. 51.39N 01.20E, 21/08/1877

BEVERLEY, Thames, E. Barrow Sand. 51.38N 01.11E, 25/11/1877

To be continued...

Reference:

Richard & Bridget Larn, (1995) Shipwreck Index of the British Isles: Index to Volumes 1-3 (v. 2). Edition. Tor Mark Press.

The names of some of those that were executed for their part in the Mutiny at the Nore, 1797

The Leopard

• Dennis Sullivan

• Alexander Lawson

• William Welch

• Joseph Fearon

• William Ross

• George Shave

• Thomas Sterling

Hanged at the Nore on Monday 10 July 1797, four on board their own ship, the Leopard, and three on board the Lancaster.

The court initially sentenced nine to death but two, James Robertson and John Habbigan were recommended to the mercy of the king. They were respited and subsequently pardoned upon certain conditions.

The Sandwich

All twenty men of the Sandwich below were condemned to death after going on trial. The trial began 6 July 1797.

• William Gregory

• Charles M'Carthy

• John Whittle

• Thomas Appleyard

• Peter Holding

• George Taylor

• Joseph Hughes

• Thomas Brady

• George Gainer

• John Davis

• James Hockless, quarter master

• John Scott, gunner’s mate

• Charles Chant, seaman

• William Thomas Jones, seaman

• Henry Wolfe, Boatswain’s Mate

• James Luran, seaman

• James Johnes, seaman

• James Brown, seaman

• Thomas Brookes, sargeant of mariners

• William Porter, private marine

Although all men were sentenced to death only five were executed. On the 1 August 1797 William Gregory, James Hockless, Charles M'Carthy and Peter Holding were executed on the Sandwich at Blackstakes and Thomas Appleyard on board the Firm brig, in Gillingham Reach.

the Monmouth

• Richard Brown

• John Doughty, sailmaker

• William Firth, ship's corporal

• Matthew Williams, captain of the maintop

• William Vance, quarter master

• John Dun, sergeant of the marines

12 more mutineers of the Monmouth were also tried, of the whole 18, the six above mentioned were sentenced to death; but two were recommended to mercy: four were ordered to be severely flogged, two to be reprimanded and one was acquitted.

On 14 August 1797 Vance, Frith, Brown and Earles were executed on board the Monmouth. About nine o'clock the fatal gun was fired, and they were drawn up the yard-arm.

Trials went on, with the mutineers of the Inflexible and Standard. 13 altogether received the sentence of death. One of the condemned men behaved in the most excited manner during his trial; and when the awful sentence was pronounced he fell upon his knees and prayed God “that his blood might fall on the head of his persecutors, and the witnesses that had appeared against him; and that the cries of his wife and children might ever be ringing in their ears.”

Reference:

Neale, William Johnson, (1842), History of the Mutiny at Spithead and the Nore with an Enquiry into its Origins and Treatment and Suggestions for the Preventions of Future Discontent in the Royal Navy (1st ed.) London: Printed for Thomas Tegg, 73 Cheapside pp. 365-399

Wednesday 19 August

Families that lived on the houseboats of Leigh-on-Sea

Vaughan and Cecile Copeland, their daughter Yvonne and son Tony lived on the Taj Mahal in the 1930s.

Albert and Ellen Lawson, daughters Winifred and Edith, sons Albert and Alfred, lived on Comet. Albert and Ellen's other daughters Ellen and Elizabeth would visit at weekends and holidays. They lived on Comet along the seawall in Leigh-on-Sea from the late 1930s to 1950 when it moved to Pitsea Creek. The floods of 1953 caused it to sink and it was eventually lost to a fire some time after (date not provided).

Reference:

Carol Edwards (2009) The Life and Times of the Houseboats of Leigh-on-Sea, Publisher Carol Edwards.

Tuesday 15 September

Prison Hulks out of Chatham and Sheerness

Here is a list of prison hulks out of Chatham and Sheerness. The list shows: name; year placed in service; estimated time in service; typical prisoner count; station:

Retribution, 1804, 30 years, 450, Woolwich, Sheerness

Zealand, 1810, 3 years, 470, Sheerness

Bellerophon, 1816, 9 years, 480, Sheerness

Ganymede, 1820, 19 years, 240, Chatham, Woolwich

Dolphin, 1824, 8 years, 650, Chatham

Euryalus, 1825, 18 years, 385, Chatham

Fortitude, 1831, 13 years, 475, Chatham

Reference:

Charles Campbell (1994), The Intolerable Hulks, British Shipboard Confinement 1776-1857, Heritage Books Inc.

bnr#68 => Lady b - mast, Leigh-on-sea

bnr#68 => Lady b - mast, Leigh-on-sea