Jean Demars - Conversations

Jean Demars, Miners Activist Posters.

My role in this project was about researching the 1984-85 miner’s strike, turning point at which coal mining is displaced to distant lands; and get different people involved in the strike to participate alongside the installation. We chose to set up stalls, as a kind of strange and dark fair, which resonates with the mix of joy present in mining culture and the anger at the events that unfolded during that time.

Process [Research/method]

I set out to Newcastle in January 2010, having never been there before… I had also been warned… If you think you’re working class, you haven’t been to Newcastle yet.

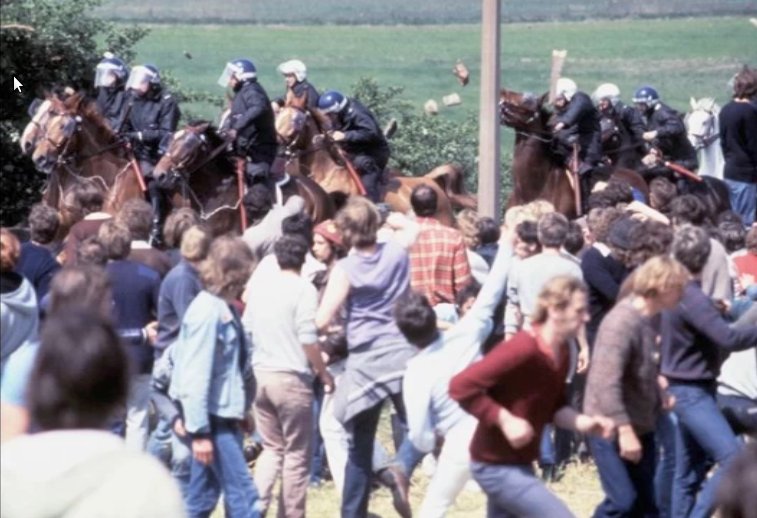

Very rapidly, I found some of the people I wanted to involve in the project. Amongst them are: Dave Douglass, who you have seen in the film, is an ex-miner on the left of union politics, anarchist at heart and from whom I learnt a great deal, not only about the history of the 1984 strike and what he feels was wrong with Thatcher’s government but also the role of the Union itself and its implications in making money on the compensation claims. Dave has been involved in union politics since he entered the mine but he also always kept a healthy distance from bureaucratic and hierarchical tendencies endemic to the union structure. The Union appears to me like an old dinosaur in its functioning today but it was not always like this. The miners strike offers us a kind of late illustration of a passage from Foucauldian disciplinary society, with a tied, solidary, loyal, proud, working class culture and its passage into free-floating control societies where people work in B&Q instead and where union and syndicalist politics have no place. The National Union of Mineworkers was helpful to provide reading material, and there is a huge amount out there, it is impressive to see how much mining culture alone could produce at the time and how active they were. Trevor came with a 3.5 tonner full of books, which we could only take a tenth of for the exhibition. I did an audio recording of Peter Arkell who had been a photographer during the strike, mostly in Yorkshire, to go with a slideshow of his pictures.

Watch the interview with Dave Douglas, Miners Activist.

The first time I went to Newcastle, I remember also hearing stories about pit towns, where the rough kids are, people telling me that you can clearly see who comes from pit towns and as I had gone around Newcastle centre already, I thought I should set off to one of them and see what it’s like.

You have to understand a certain context in the North East where Newcastle has received a lot of regeneration money and where that agenda is driving forward many programs, so that mining might be forbidden to mention in certain projects… People want to move on from those days we are told. You will also easily see the difference if you go down half an hour on the train and get to Sunderland where the regeneration money has not reached there quite as much. And then you have Middlesbrough which is now the cheapest place to live in the UK, and that is because there is not much other than old factories and abandoned industrial estates.

I arrived in Easington, a pit town that had been under Police siege during the strike, and of which you can see images taken at the time by Keith Pattison, who was a photographer part of a collective called Amber. Their work is rooted in social documentary, built around long term engagements with working class and marginalized communities in the North of England. They have worked in those communities since the 1970’s. I recommend SeaCoal if you haven’t seen it. Keith spent the length of the strike in Easington testifying through his images. There is nothing left of the Easington coal mine but a mount, and a tiny bit of the shaft coming out of the ground. What used to be the focal point for that community is today no more than a mere viewpoint on that community. Roles have been reversed, except that the community is not as productive and conducive in itself as the mine was back in the days. A little bit further down from the main pit, there is another pit, which has become a golf course. A bit further down again, another has become a B&Q, ironically. But the reason I have wanted to talk to you about this particular town is for two of its women: Marilyn Johnson and Heather Wood. They were at the heart of what the strike was about: community politics Vs state politics.

Watch the interview with Marylin & Heather, Miners Wives, Activist.

[The hatred they develop for Margaret Thatcher is best encapsulated in Marilyn’s act on the day the strike ended. She bought a bottle of Champagne. 25 years on, the bottle is still lying in her fridge, waiting for the day Maggie’s going to die.] Dave told me in an interview that what most miners had to fight against during the year’s strike was not the Police, even though there was much violence, it was only a tenth of 200’000 miners who ever went on the picket line. No, what they fought against was the cold, the hunger, thinking about how they were going to feed/clothe their kids. That is where the role of women during the strike becomes so important. They set up a Free Café, working every day of the week for a whole year to feed up to 500 people at a time, but also clothe, campaign, raise money, etc… The women of the strike are the element that enabled it to last for so long and keep the communities together for that length of time, as the café was not only a feeding place but a discussion, planning and organizational ground. What that did for these women who came from quite machist communities, was amazing and they grew from that, relationships between men/women would be changed forever there. Their way of recounting these events is also amazing because it is so personal, they remember each and everyone’s name. Their ideals are so practical that they have stopped being ideas and have become practices of resistance, practices of community empowerment, practices of community in the making.

Watch the interview with Rachel Horne, strike baby, artist.

The last participant I want to mention is Rachel Horne. Rachel is a young artist, strike baby and Thatcher baby all at once with a passion for her community, which she developed when she came down to London to escape from it. And she helped me to understand the generational issues associated to the miners strike and to CFC more generally. How is it that in a country like Britain, kids and teenagers don’t learn about the miners strike in school? How is it that they don’t know how their computers, video games are made? How is it that what their parents lived and fought for has become so insignificant? How is that those prosperous towns have become ghost towns?

Concepts [that came out of this research]

Watch the interview with Peter Arkell, Strike Photographer..

One of the major concepts that came out of both the miners strike and CFC is the notion of displacement. And it became also the most difficult thing to visualize. Miners knew 25 years ago that the closure of mines in Britain was not the end of coal, but its displacement to distant lands where working conditions would go back 200 years in time and the consequences of the loss of coal mining would have on communities in the UK, many of those being slowly emptied out of their productive force, not only materially but socially and more importantly culturally. Miners dying in accidents were recorded in Britain as early as the end of the 18th century. In India and China, there are no such records, and that is because despite nationalized mines showing records of occupational safety and some deaths (they are only recorded if they are superior to 6), most mines are worked illegally by men, women but also children. So coming back to our notion of displacement, that meant we had a kind of black hole that was at the same time the lifeblood of our knowledge economies. How do records affect our conception of events? What happens when things don’t get recorded? How does the non-recording of miners in India or China affect our understanding of control societies here in Europe? Is this apparent lack of control or lack of interest in human beings becoming mere bodies of flesh fit in with our idea of control societies? Just as capital needs poor people to produce wealth, striving on blatant inequalities, control societies may need unrecorded data to make its own data relevant.

The other aspect of the project I would like to address is that of engaging marginalized groups, or communities and what we tried to do with it.

Community Arts is always appropriated by NGOs for social inclusion and its associated good governance discourse. Always attached to a notion of the good. In this case, we had no agenda of social or economic regeneration: we wanted different elements of the community to participate on their terms, even if we asked the questions. I left it as open as possible and did not constraint them very much. Art is no therapy either so our project doesn’t have the feel good factor that many art projects working on the margins would have. It is also much more difficult that way to approach people and ask them to participate on a project where sick flesh is resuscitated by what killed it in the first place, and speak up on what they lost and never quite recovered from. Many men won’t talk about the strike anymore as it became a trauma to their pride. The collaboration that took place between the various elements of the project was at times conflicting and other times seemingly disparate. But there was never any intentions on our part to make an overarching argument. It was more about putting those various elements in close proximity and let both audience and participants make it up for themselves. I think there are two concepts that arise out of this practice. One is Matthew Fuller’s media ecologies, which helps us to think about how a system is always complex in nature. The other concept that comes out of these collaboration and ecologies is that of Crisis. I am very aware that crisis has become an ubiquitous concept in many disciplines, whether we talk about humanitarian crisis, financial crisis or ecological crisis. But I would like to put a positive spin on the concept and see it as something that happens every time a system undergoes change through the juxtaposition of different elements, affecting one another and changing each other in the process. So what I would like to say to finish with is to not just let these crises happen but create them, and trust in the openness of the system. Against crisis management which leads us to the next crisis and makes sure nothing changes… It would have been fascinating to have involved some of the lawyers who made millions on the back of miners claims, although I doubt they would have come. That could perhaps be a direction to push the work further by putting different elements in this kind of uncomfortable proximity.

bnr#44 => Invisible Airs, Database Security Access, Council Building, Bristol, UK

bnr#44 => Invisible Airs, Database Security Access, Council Building, Bristol, UK