Invisible Airs, Database, Expenditure, Power

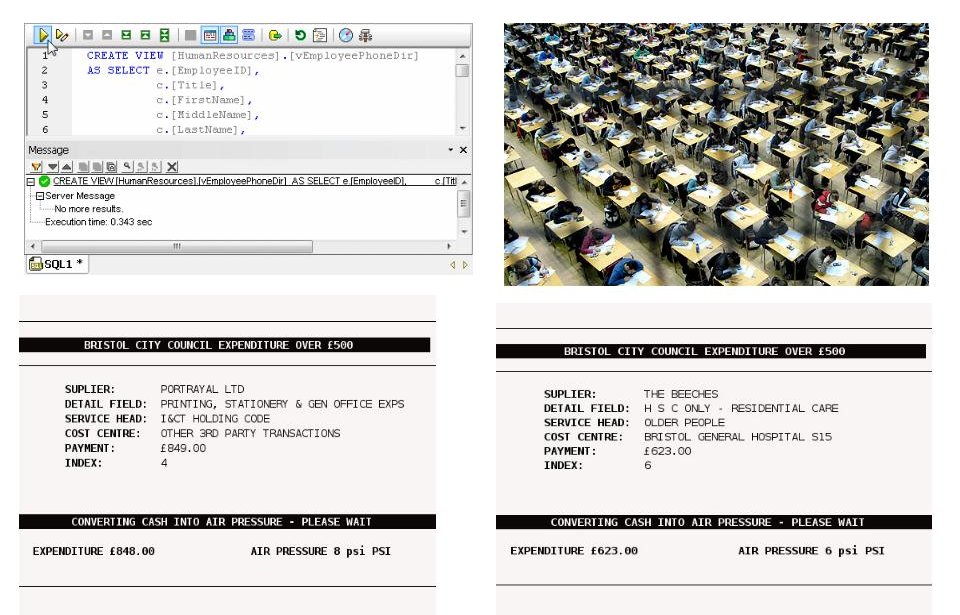

It is possible too that the technological has its own set of imaginings. And I want to introduce three of them here, that of databases, pneumatics or compressed air, and the idea of the contraption, the unruly exuberant machine of experiment. Databases move through us, allowing new forms of power to emerge from the machine’s ability to push and process large sets of information into the gaps between knowledge and power. As databases order, compare and sort they create new views of the information they contain. New perspectives amplify, speed-up and restructure particular forms of power as they supersede others. A database is however, not a single machine, but one that carries within its genes the echoes and residues of its former selves.

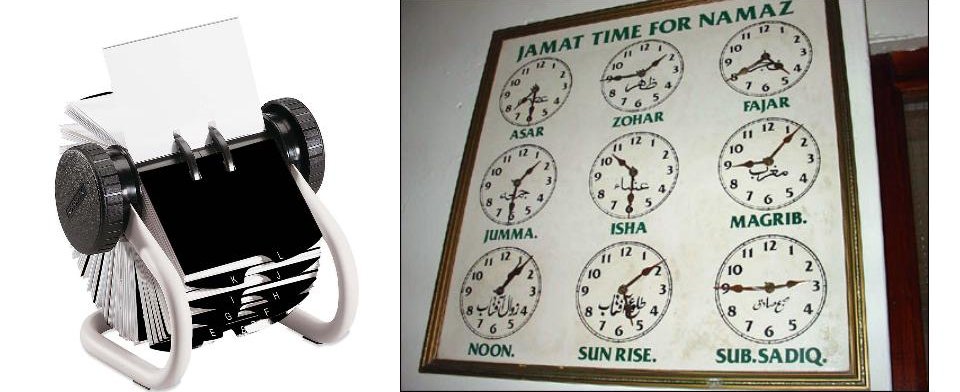

Amongst the things stuffed into the workings of Bristol City Council’s Databases, is the town hall clock that allowed people to be coordinated into a single machine, it reappears in date-time fields and allows us to search for what happened when. Rolodex and index cards systems appear as unique identifiers allowing relationships between the information they point to. The accountants ledger with its rows and columns arranges the data across the screen. The triangulation of terrain, maps for empire, reappear as post codes, electoral boundaries and other geographies.

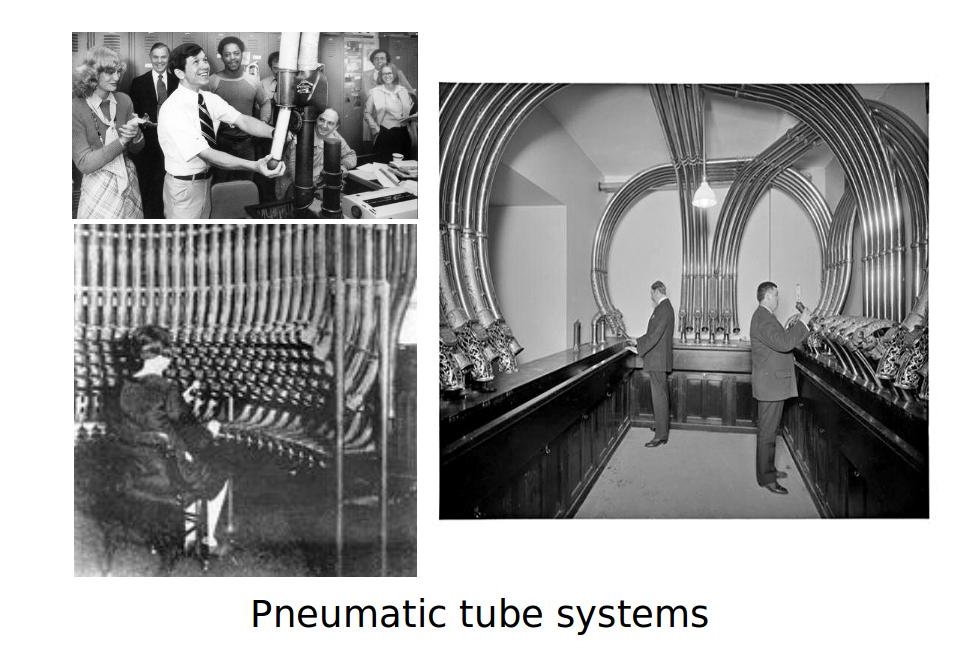

Compressed air, tunnelling, boring into roads, ditches, quarries - mud, filth, making pathways for communication, high speed fibre optics and municipal plastic pipes full of shit, it batters rocks to pieces, loads things and unloads things. We sit on its pneumatic tubes – atmospheres under pressure while we jog along in our little riding machines.

Pneumatic tube systems used to push data around 1850's telegraphic bottlenecks, sucking and blowing messages between The Central Telegraph Office and the Stock Exchange, between Fleet Street, where newspapers were written, and the nearby City of London.

The standard atmosphere is 14.696 bars per square inch, while our lungs compress air at 2.9 pound-force per square inch. 10800 litres per day 500 ml X 15 breaths/minute x 60 minutes/hour x 24 hours/day. Air moves between us, first inside you, then inside me. You hear me through it, you smell me through it, we pass infection through it.

In the 1880's Victor Popp was given a 50 year contract for the pneumatic distribution of time across Paris. Pointers on clock faces changed, aligned by a pulse of air sent every minute, coordinating the opening and closing of a city.

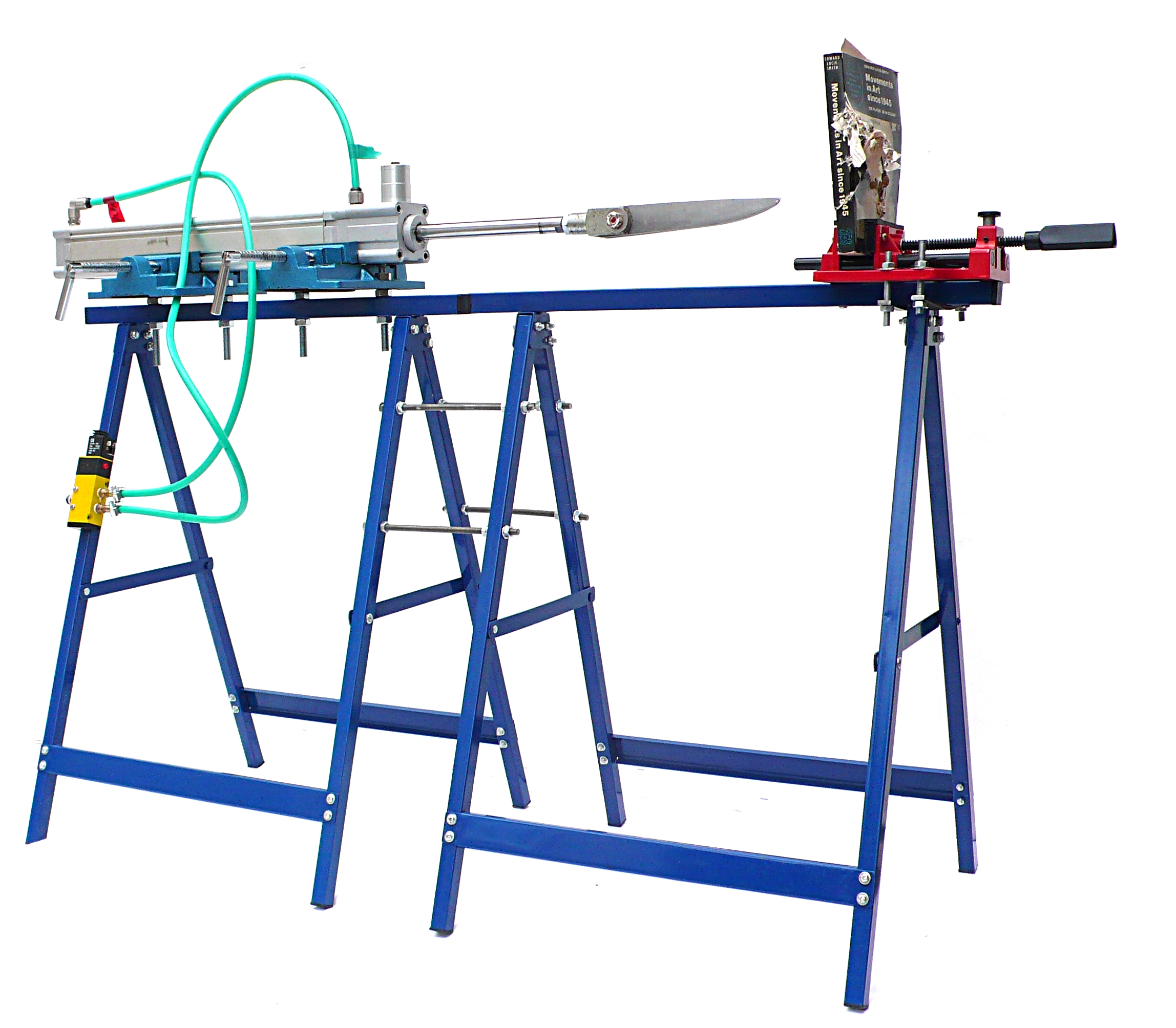

Contraptions create mechanisms by which useful machines can exist, safely, securely and dependably. The term invents a space between the insane and the reasonable uses of machines and the forms of energy that power them. A pneumatic open-data book stabber is a contraption while a nuclear submarine is reasonable. The word contraption is often applied to what seem to us as illogical, barbaric, redundant, violent uses of machines, and assemblages of machines and their energies. In this way a contraption also calls into question the validity of the inventor, producer, or manufacturer of the machine. This process usefully scopes out a space between technological risk and security, creating a space in which the technological can mix freely with rather unhinged imaginings.

18th century Bristol dock - Specimens

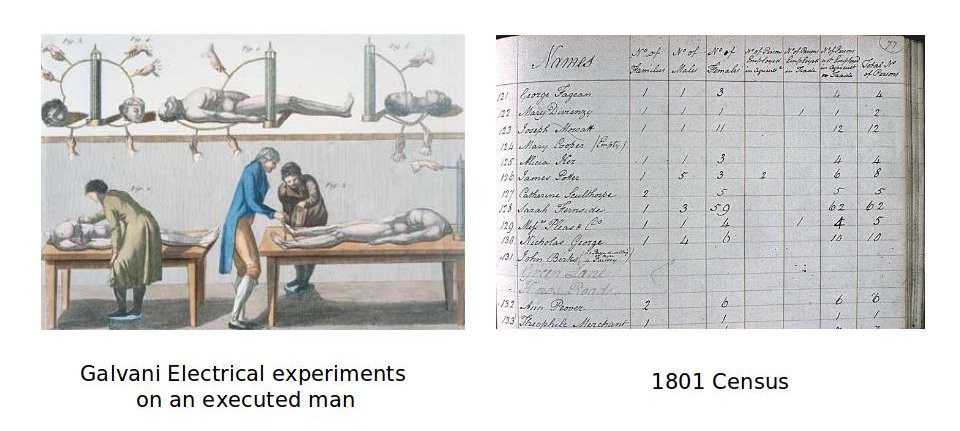

Heaps of exotic dead and near-dead things arrived in the late 18th century Bristol dock. Some chained together and stored in caves, some beaten on and off ships, others stored in boxes and sent up to London. Iced, electrocuted, stuffed, dried, dissected, pickled organisms were being measured, prodded and probed, put into categories and placed into the neatly ordered rows and columns of the species case.

Databases can also be unfolded back to the emergence of population management of the early 19th Century in which public health, small pox vaccination, food scarcity, census amongst others had created new technologies of data collection, interpretation and control.

John Rickman a 1798/99 clerk to the House of Commons, put forward the Census Act in 1800, also known as the Population Act, which outlined systems for the gathering of the intimate knowledge of a country.

The first census in the UK in 1801 promised to discover, order and discipline population in a similar way to the specimen case. In revealing a population’s components, it created a new kind of knowledge that could act as a kind of remote control on the elements it defined. How many people can be press-ganged onto British Navy ships from the Thames Estuary in Essex without destroying food production for London? What is the least amount of corn I need to produce to feed the population of Manchester or Liverpool and avoid social unrest? The trajectory of the 1801 census was to create a machine in which the mechanisms of governmental power would function fully, creating a state of readiness.

The mechanisms of recording, ordering and regulating information require containers to be constructed, boxes that discipline parts by saying what they can and cannot hold. In this way constructing a container a record called ’street’, calls into question the legitimacy of living in the sea, or in a forest, or on the moon or, in the case of gypsies, by the side of the road. The empty container implies the existence of the object that it is supposed to posses. In the boardrooms of nascent empire, the containers devised for population were juggled into new machines to fight wars, famines and plagues, eventually becoming more important than the objects they were meant to contain. They began to articulate government’s relation to population.

These new powers opened us up like voltaic piles opened up the corpses of criminals in the early 19th Century. Bulging batteries urgently discharging into us, operating on us and through us till empty.

Power changes things by changing the conduct of substances through which it flows or on which it acts.

As an example: The UK Customs & Excise collects billions of pounds in revenue each year in VAT, other taxes and duties. Such work requires some of us to become rapid data entry clerks, with white knuckles bending muscles and sinew flicking fingers at a consistent 9,000 to 12,000 keystrokes an hour. Often the way a power acts on or operates through a substance is how we notice the changes it makes. Keystrokes are recorded and analysed, line managers count and assess average keystroke ceiling rates. If you type hard enough for long enough, it’ll trigger a bonus, bending the flow of power into an extra cheesecake for the family at Tesco – its acquisition triggering another flow in and out of our extended minds and actions.

If we think about government as a series of tactics, strategies, techniques, programmes and aspirations of those authorities who wish to control, influence or improve what we think of and do as a population, databases inform various modes of thinking, decision making and acting.

A zone of governance, like Bristol City Council, defines itself by the reach and liability of just such an administration. It draws up geographical boundaries by defining where it is not. In the UK, according to the Office of National Statistics, we have many such overlapping geographies, postal, health, census, UK electoral, European electoral, super output areas, travel to work areas, registrations districts, training and enterprises zones amongst them.

This civic machine polices populations by folding many of the 19th century technologies of power into its server racks, speeding up its processors, amplifying its forms of truth, justifying itself by setting up services to compensate for a primal market Darwinism.

The base layer of this civic operating system, how it knows where it is, and what day it is, derived from early conquests of space and time. Victor Popp aligned Town hall clocks are here as well as the mapping that built empires and won resource wars in the 19th Century. A set of systematic technologies capable of subdividing time and triangulating space into equal chunks. Placing snapshots of land, populations and resources into containers, magnifying them for comparison and re-assembly to survive the next round of spending cuts, war or plague.

In this way we can think of a municipal authority as a complex social, technical, administrative machine powered by the formation of 'truths' pinned on timely maps. In this instance, civic 'truth' does not necessarily have to be true for everyone. So long as it's 'true' for those who take part in the system of its production, regulation, distribution, circulation and operation of it's authoritative statements.

This form of 'truth' operates on us and through us, something like the way a doctor has the power to open you up for inspection, place a camera inside you and tinker with your organs, pull bits off for biopsies to be inspected by other powers. The doctor derives authority from all those exams she sat which enables her to manifest the collective 'truth' manufactured by medical discourse. Receiving back expert judgements about the samples collected from my colon, she has the authority to tell government that I do not have to go to work, that I'm mad, or do or do not deserve a mobility allowance.

Only certain roles can make truth and those who inhabit them, unlike data entry clerks, are paid handsomely for doing so. They are initiated into truth machines, by moving through control systems, check points, security systems, peer review, promotions. They maintain, house, add to, update and sort the truth. They initiate others into their fold, protect them, give them permission to utter the truth and most importantly wheel the machine out into the public to pronounce its legitimacy.

Databases are transducers of knowledge and power rapidly moving through us, separating us, reforming us, folding us up into their parts. Its relations and queries pick us up, move us around and put us back down somewhere known yet unfamiliar.

In the basement of Bristol City Council House is one of the aftermaths of this turning around, a series of vaults without valuables, cash desks without money and entrances without people. Something happened, something changed, money became vaporised into digits on a screen, the public banished to dark corridors of form-filling network protocols, housing benefit forms stacked to overflow in the always open, discarded vaults. Value has been redistributed into the knowledge machines of the clean room, contained in water-cooled computers fed by the decorative yet protective mock moat running around the front of the building at college green.

A new relational technology reconfigured these rooms, rebuilt partitions, redirected the flow of air, laid cables and constructed new doors, security systems to conjoin us with information released through the grant tables of our role based permission structures.

To conclude this part of the talk I want to share three notable stories of database's, power, governance. The first is how a critical approach to open data can save lives or at least find out where they are being needlessly lost. The second is how a database can reorder peoples conduct without being implemented and the third is how the machine of governance through a ingenious dislocation of surveillance renewed itself after the MP's expenses scandal.

16 years ago, Professor Brian Jarman joined others in creating The Hospital Standardised Mortality Ratio which revealed, among other things, that even when controlled for variations like patients age or class, English mortality rates differed up to 76 per cent between area to area. Dr Foster the company he set up has been publishing this mortality data since 2000. The HSMR is a calculation used to monitor death rates in a trust and is based on a subset of diagnoses which give rise to 80% of in-hospital deaths.

In 2009 Dr Foster Intelligence revealed that Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust had a mortality rate a third higher than the national average: about 350 more people died in a year more than would have been expected, leading to enquiries that revealed the appalling state of Basildon Hospital. When databases find a critically responsive audience they introduce new forces into the technologies of power.

On a recent trip to Bristol working on ‘B-Open’, we were shown around the basement of the City’s Council House. Large open-plan offices set in the now vaporised finance area of the council in which people used to pay their rents and rates. The rooms were as dull as to be expected in the seat of power but at each entrance to a subsection was a card reader. We constantly had to bother someone to move from one regulated area to another. When I asked what was at the core of this regulation I was told that it was in readiness for the introduction of ContactPoint a database established by the previous Labour administration to improve child protection after the Victoria Climbie child abuse scandal. ContactPoint was to hold the records of over 11 million children in danger in England was scrapped by the new Conservative and Liberal Democrat government.

Peoples conduct was being ordered by the potential knowledge/power relation of non-existent machine.

In it's attempt to convince us about parting with or not complain to much about the use of our personal data, government has set up a number of open data initiatives. A recent high-profile case would be the publishing of MP's allowances. The website mpsallowances. parliament.uk allows anyone with an internet connection to view all the MP's expenses in something resembling a software panoptican, an equal gaze over all the MP’s allowances in which anomalous spending of the bad may be foregrounded against the normal spending of the good.

A gaze such as this is normally associated with technologies of power in which population can be policed for health, crime, security or be quickly made ready for war as we saw earlier. Governance witnessing the effectiveness of the gaze as a technology of power, turned it on itself as an inoculation against the infection carried in by it's parasite MP's. Governance in this way appeared to martyr itself in a public atonement for it's infection. In acknowledging and reflecting on it's own subjugation before the relational machine the government enables this technology to amplify it's power to create ever larger machines. Look we did it to ourselves, we are all in this together. The equal gaze afforded by MP's expenses databases is a set of truths, a register of moral victories on which to build the next round in the arms race of technologies of power.

I have no doubt that the love dance of database's, power, governance will end up producing a new kind of tyranny, not the exciting cold war ones, surveillance and secret police. More probably the dull one that chains rapid data entry clerks to sweaty keyboards, checked for key presses every minute – awaiting that illusive extra cheese cake. Whether it will be any better or worse then the tyrannies that have gone before is hard to tell, but the journey will be interesting. As databases open us up, operate on us and through us and append us into their parts, they will disrupt and dislodge much of the authority we see around us replacing it with new forms of power and authority made possible by their invention.

bnr#54 => Invisible Airs, Contraptions, Bristol, UK

bnr#54 => Invisible Airs, Contraptions, Bristol, UK